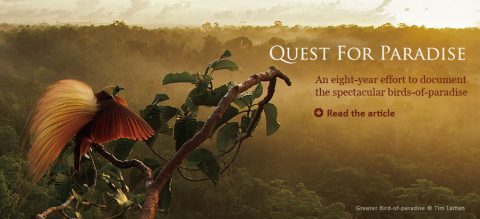

The Bold and the Bashful: the Personalities of Backyard Birds

By Abby McBride, Photo by David Kjaer/NPL/Minden Pictures

October 15, 2012

Spend enough time watching chickadees at your feeder, and you might start to recognize individuals by their behavior. Maybe one chickadee acts like a little tyrant, monopolizing all the food. Another chickadee might have a penchant for skulking timidly on the outskirts.

If you think feeder birds have personalities, you’re not imagining things. In recent years biologists have tested animal personality in everything from mammals to mollusks, showing that individuals really do have consistent differences in behavior. But we’re still learning why those differences matter in the wild. What’s the point of having a shy personality, for instance, if it makes you miss out on a meal?

A European bird called the Great Tit—which looks like a chickadee dressed up in a yellow vest—recently shed some light on that question. When Oxford biologist John Quinn and colleagues experimented with a wild population of 156 individually tagged Great Tits, they found that being shy isn’t always a bad thing, according to their paper in The Proceedings of the Royal Society. First, Quinn identified each bird’s personality type by testing how many hops and flights it used to explore an artificial space. He knew from previous studies that this behavior would be a good measure of overall personality: the slapdash explorers tend to be bold and reckless, whereas the slow-but-thorough explorers are usually timid.

Once he had gauged the birds’ personalities, Quinn wanted to see how they behaved in the great outdoors. So he set up two bird feeders 30 feet apart in the woods, putting one in a “dangerous” spot out in the open. The second feeder went in a “safe” spot near dense shrubbery, where the Great Tits could hide from Eurasian Sparrowhawks.

Quinn stocked the safe feeder with whole peanuts and put less-appetizing nut granules in the dangerous feeder. He kept track of how much time individual birds spent at each feeder in the morning, when they were hungriest, and in the afternoon, when they were less hungry. Unsurprisingly, most birds visited the safer and more enticing food source, regardless of the time of day—until Quinn pulled a switch.

He swapped the desirable food into the dangerous feeder, forcing the Great Tits to make a choice between eating well and being safe. Quinn found that the two personality types approached this predation-starvation tradeoff in opposite ways. Adventurous birds risked their necks to fill their stomachs. But cautious birds stuck with the sheltered feeder even in the morning, risking starvation to stay safe. “It’s the first evidence, really, that they handle these risks differently in the wild,” Quinn says.

Both strategies have advantages, in theory. A shy bird is more likely than its bolder compatriots to die of starvation when food is scarce. But the same bird in an exposed site is less likely to wind up as a sparrowhawk’s lunch. André Dhondt, director of Bird Population Studies at the Cornell Lab, says that the world is an uncertain place for a Great Tit, full of shifting dangers. That’s why both adventurous and cautious birds survive in a population.

Quinn has not yet tested whether these survival behaviors are actually translating into life or death for the Great Tits. But he does know from previous research that Great Tit personalities are partly hereditary, which suggests that each bird’s behavior choice—whether to venture forth or stay hidden—has been molded by natural selection.

So the next time you see a shy chickadee getting edged out at a feeder, don’t worry too much: it just might be shy for a reason.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you