By the Waters of Kariba, a Manmade Lake in Southern Africa

Text and photographs by Chuck Graham

July 15, 2012

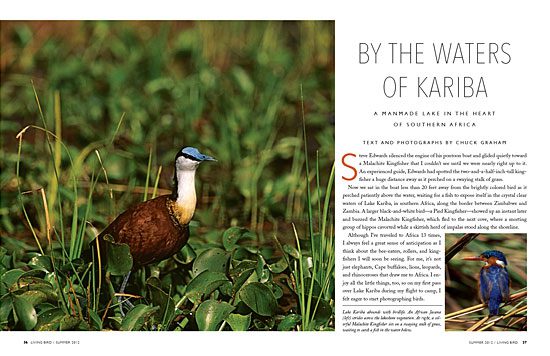

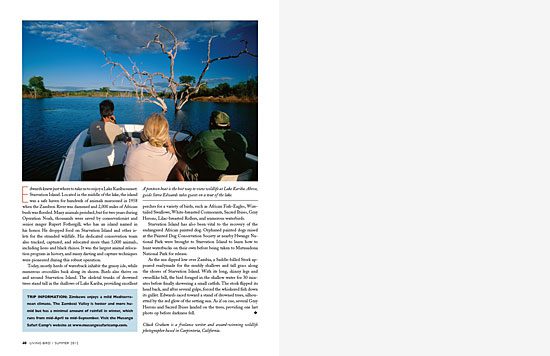

Steve Edwards silenced the engine of his pontoon boat and glided quietly toward a Malachite Kingfisher that I couldn’t see until we were nearly right up to it.

An experienced guide, Edwards had spotted the two-and-a-half-inch-tall kingfisher a huge distance away as it perched on a swaying stalk of grass. Now we sat in the boat less than 20 feet away from the brightly colored bird as it perched patiently above the water, waiting for a fish to expose itself in the crystal clear waters of Lake Kariba, in southern Africa, along the border between Zimbabwe and Zambia. A larger black-and-white bird—a Pied Kingfisher—showed up an instant later and buzzed the Malachite Kingfisher, which fled to the next cove, where a snorting group of hippos cavorted while a skittish herd of impalas stood along the shoreline.

Although I’ve traveled to Africa 13 times, I always feel a great sense of anticipation as I think about the bee-eaters, rollers, and kingfishers I will soon be seeing. For me, it’s not just elephants, Cape buffaloes, lions, leopards, and rhinoceroses that draw me to Africa. I enjoy all the little things, too, so on my first pass over Lake Kariba during my flight to camp, I felt eager to start photographing birds.

Lake Kariba is a manmade lake created when the massive Kariba Hydroelectric Dam was erected on the Zambezi River in 1958. It took about five years to fill the lake, which eventually flooded the Kariba Gorge. It was a controversial project at the time, displacing people and wildlife, but the area now seems to be thriving.

Before Lake Kariba was filled, the existing African bush was burned, creating a thick layer of fertile soil on the land that eventually became the lake bed. Matusadona National Park lies on the southern shore of Lake Kariba, bounded to the west by the Umi River and to the east by the daunting Sanyati Gorge. It is home to herds of elephants, cantankerous Cape buffaloes, endangered black rhinos, prides of lions, solitary leopards, waterbucks, greater kudus, impalas, and 480 species of birds.

“Lake Kariba is actually a manmade structure that works,” says Edwards. “There is year-round water for all to access.”

Those include villagers with their livestock from Zimbabwe and Zambia. The lake is also important for fishing and contains 42 species of fish, including nkupe, chessa, bottlenose, vundu, barbell, tiger fish, catfish, and bream. African Fish-Eagles and a bevy of waterbirds also enjoy the diversity of fish.

Edwards is a keen birder and photographer and has been a bush guide in Zimbabwe for 35 years. He spent 18 of those years working for the Department of National Parks and Management and four as a warden at Matusadona National Park, where he was head of an antipoaching unit. He retired in 1990 and built his Musango Camp from the ground up in 1992, just offshore from Matusadona National Park. The shaded, permanently tented camp has 360-degree views of the lake and is frequented by Nile monitor lizards, crocodiles, wallowing hippos, and Gray-headed Kingfishers. And to keep the guests on their toes, several resident vervet monkeys run amok on the isle.

A few years ago, in one 24-hour bird count, Edwards and several other birders spotted a record 252 species of birds from his pontoon boat, the best craft for birding and photography on Lake Kariba. Yet, after all of the time he has spent in the bush, several species—such as the especially uncommon White-backed Night-Heron and Pel’s Fishing-Owl—have eluded Edwards’s 300mm lens.

“It’s one of the many reasons I love it here,” said Edwards. “You can see something you didn’t see the day before.”

As hard as we looked at dawn and dusk, we never spotted the strictly nocturnal Pel’s Fishing-Owl, but we did find a White-backed Night-Heron by accident.

While cruising past a seemingly lifeless cove, we spotted the remains of a songbird, its fragile skeleton dangling on the threads of an old golden orb spider’s web. These gangly spiders aren’t venomous, but the webs they spin are as thick as threads and sometimes snag small birds.

Our attention was diverted toward a disturbance in a giant succulent leaning out over the same tranquil, shaded cove. A White-backed Night-Heron crept over the elongated stems, momentarily revealing itself. More comfortable at night, the elusive waterbird tried to hunker down when it saw us. We sat quietly in the boat, hoping that the bird would come out of hiding, but instead it burst into the air, emitting a toadlike kraak call as it flew away, quickly vanishing from sight.

Another bird we had hoped to see was a Scarlet-chested Sunbird. In one of the deeper coves, choked with dense African bush, we found a succulent with pretty red blooms.

“Let’s wait and see if one flies in,” said Edwards. The red blooms swayed gently back and forth in the wind as we watched. Several Little Bee-eaters flitted across the dense vegetation as a Striated Heron climbed robotlike on a dead tree wedged into the red earth against a steep embankment.

As the wind died down, we spotted our first Scarlet-chested Sunbird, a female that we had heard repeatedly calling—cheep, chip, chop— from the branches of a nearby baobab tree before it dropped down and began foraging, sticking its curved bill into each bloom to get the nectar. Though we waited for a while, 50 feet away from the blooms, no male sunbirds showed up.

Pick any cove, sit and wait, and it will eventually come alive. One morning began with a pair of White-fronted Bee-eaters taking turns nabbing insects from a perch on a tree. Edwards quietly drove his pontoon boat up a muddy embankment, turned off the engine, and we watched. Before we knew it, an African Pied Wagtail flew in beneath the beeeaters as they picked insects from the ground. Minutes later, a raucous pair of Southern Yellow-billed Hornbills arrived and shared the tree with the bee-eaters. Then a two-foot-long Nile monitor lizard clawed its way from underneath a bush and sprawled in the mud to soak up some sunlight. In the shallows on the starboard side of the boat, an African Jacana nimbly ambled over lily-covered pans. And then we heard a spectacular Martial Eagle, thrashing through the trees above the water and calling—kloo-ee, kloo-ee. Edwards steered his boat in the direction of the sound so we could get a look at the juvenile eagle, which was perched in a cluster of leafy trees. Its piercing eyes met our lenses for several seconds before it awkwardly flew out of our sight.

Our next wildlife encounter was a study in how an ecosystem works together, with one species skating on the coattails of another. As the engine fell quiet and we drew closer, we could hear water filtering through wads of soggy green grass as a huge bull elephant yanked stalks of Panicum repens from the shallow water with its trunk. Edwards got us to within 20 feet of the hungry old bull. It was missing a tusk and shook the grass before munching on the nutrient-rich stalks.

What was interesting to observe was the flock of Cattle Egrets busily foraging beneath the elephant, quickly maneuvering between its legs while carefully avoiding the tusker’s heavy steps in the muddy shallows. The birds feasted on a plethora of insects, fish, and reptiles stirred up by the elephant as it gorged.

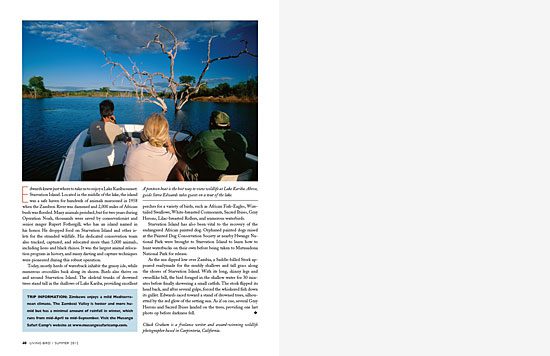

Edwards knew just where to take us to enjoy a Lake Kariba sunset: Starvation Island. Located in the middle of the lake, the island was a safe haven for hundreds of animals marooned in 1958 when the Zambezi River was dammed and 2,000 miles of African bush was flooded. Many animals perished, but for two years during Operation Noah, thousands were saved by conservationist and senior ranger Rupert Fothergill, who has an island named in his honor. He dropped food on Starvation Island and other islets for the stranded wildlife. His dedicated conservation team also tracked, captured, and relocated more than 5,000 animals, including lions and black rhinos. It was the largest animal relocation program in history, and many darting and capture techniques were pioneered during this robust operation.

Today, mostly herds of waterbuck inhabit the grassy isle, while numerous crocodiles bask along its shores. Birds also thrive on and around Starvation Island. The skeletal trunks of drowned trees stand tall in the shallows of Lake Kariba, providing excellent perches for a variety of birds, such as African Fish-Eagles, Wiretailed Swallows, White-breasted Cormorants, Sacred Ibises, Gray Herons, Lilac-breasted Rollers, and numerous waterbirds. Starvation Island has also been vital to the recovery of the endangered African painted dog. Orphaned painted dogs raised at the Painted Dog Conservation Society at nearby Hwange National Park were brought to Starvation Island to learn how to hunt waterbucks on their own before being taken to Matusadona National Park for release.

As the sun dipped low over Zambia, a Saddle-billed Stork appeared readymade for the muddy shallows and tall grass along the shores of Starvation Island. With its long, skinny legs and swordlike bill, the bird foraged in the shallow water for 30 minutes before finally skewering a small catfish. The stork flipped its head back, and after several gulps, forced the whiskered fish down its gullet. Edwards raced toward a stand of drowned trees, silhouetted by the red glow of the setting sun. As if on cue, several Gray Herons and Sacred Ibises landed on the trees, providing one last photo op before darkness fell.

All About Birds is a free resource

Available for everyone,

funded by donors like you